|

We're lucky, as a family who play various instruments, we can make music together every few months in this COVID-19 time for our neighbors and friends who come masked, bring their own chairs and sit socially distanced. Our sons play bass, drums, our daughter has been teaching ukulele, guitar, cello, and our niece, violin, electric violin, voice. Mindful of how blessed we are, and wishing the best health and safe environment for everyone else.

0 Comments

This is an invitation to an adventure in awareness, an approach to the experience of living that only makes living more real.

Let’s take a breath. At any moment, we can be home, and home is much closer than we think. If we can just realize the reality of THIS breath, we can be at home right now, in our body, just as it is, without commenting on how it should be. Take another breath, eyes closed………………… … then another. There is a way of being, a way of paying attention that is fresh, like coming out of a womb, like tasting lemon for the first time. To explore it as a pure idea would be an exercise in thinking, an exercise without life. Check in with your body; live the fullness of THIS moment. Let's take three breaths eyes closed. “What am I sensing?”. See for yourself how things change as you pay attention. Did you hear the leaves? the lightbulbs? Did you see shades of black inside your eyes? Did you notice an itch? Did you discover a scent? What sense was most prominent? Let's take four breaths and zone in on another less prominent sense. Though these acute senses brought you superpower, we are more than our body. We are more than our emotions. We are more than our thoughts. Let's take five breaths eyes closed and discover where our thought goes when it’s roaming. Let it roam. Just follow the bread crumb like a drone, without judgment. With stillness, we can catch our thoughts as they’re passing by. That’s what’s peculiar about thoughts, they all do that, passing by. Nothing human lasts forever. If you enjoyed your breaths, take a few more This very minute could feel like the first minute… of the rest of your life. Here’s a chance to begin anew. If you enjoyed breathing more than reading, take a few breaths Your life is already doing the doing itself. You don’t have to do the living. You’ve just spent 5 minutes living to the fullest. Take one last breath No one can tell you what your path is. There is not just one way. There are manifestations of ways. Whatever ways we find, there you are. Sometimes there are moments of not knowing. Just as silence is as integral to music as sound is, these unfolding moments are part of your own song. Find comfort in uncertainty. Through my students, I learn that there are many types of Mindful practice that could help them.

1) Breathing before an important performance slows down heart rates, doing it while walking towards the piano helps focusing on body and mind as opposed to others and noise in the room. Once the student sits, he or she can mindfully (still following breathing) put hands in position, check on body position, (sitting too far, too close, too much to the left or right...) and listen to the silence and inner pulse or sounds before producing the REAL sound, which will seem miraculous because there was intense listening to silence right before! 2) Being mindful of our own speed, means to simply hear/feel a pulse AS IT IS! Easier said than done, as youngsters tend to speed up and often count at a certain speed before playing, and then pick up another speed when they actually play! If OUTSIDE of sitting with their instrument, students express that speed through walking, moving to a slower pulse, and subdividing with mouth sounds, or hand/head gestures, then they'll absorb that speed more. Experiential learning, body absorbing concept rather than intellectual counting. Many transfer students come to me counting perfectly, with the 1 matching what notes fall there, and the "and" matching which notes fall there, and so on. But this does not necessarily mean the rhythm was correct! 3) Being mindful of how children are impressionable: Sometimes we grossly exaggerate what happened in our mind when we made a mistake. Focusing on WHAT REALLY happened helps students stay with REALITY. Recording themselves is the first step. But some will still be bias while listening to themselves on the phone IF they do not let a lapse of time pass before they do the listening. I often ask students, right after they play the whole piece: So, tell me what you did well, and what needs work? forcing them to reflect, rewind, re-evaluate, and gain critical thinking. Mindful of how a mistake can be translated into a "do or die" attitude, I often do improvisation with them to show that mistakes can be corrected to something else, and that in improvisation or creation, there can be NO mistake! That is the attitude I wish for parents of my students. Tom Sawyer somehow convinced Ben that whitewashing a fence is not a dreary task but a privilege. Many boys later joined in the "fun" and whitewashed the fence for Tom. WORK is what one HAS to do, and PLAY, what one WANTS to do. Mindfulness is a twisted light that can transform a mundane ordinary task into an enjoyable PLAY time. All it takes is a few breaths, a focused attention on what one is really doing, a fully lived sensory experience of life and thoughts as they unfold. A study of preschoolers during their play time suggests that giving an extrinsic reward to one group of toddlers (for drawing during that period) actually decreases their desire to draw two weeks later. Those who did not receive any rewards or received unexpected rewards are the ones who maintained their drawing interest. (1) Another study of school children found that those who are paid to solve problems typically choose easier problems later on, and therefore learn less.(2) The short-term prize pushes out the natural human curiosity and long-term learning goals. A panel of curators and artists rated artworks on creativity and technical skills without knowing whether the work was commissioned or not. The commissioned works are rated as significantly less creative, but equal on technical skills. Artists say “doing a piece for someone else, it becomes more work than joy.” (3) This does not necessarily mean that all rewards will have negative consequences in the long run. A reward NARROWS our focus. That’s helpful when there is a CLEAR path to the solution, an existing formula or a fixed number of instructions to a logical conclusion. Rewards boost performance in routine tasks: one route to one solution. But rewards are terrible to problem solving that requires experimenting with possibilities in order to find a new solution. Heuristic tasks require seeing the periphery, having flexibility to adapt, creating connections where there were none, and absorbing conceptual understanding. In the 20th century most work were routine. Now those types of work are either outsourced or done with machines. Art, thankfully, is full of heuristic tasks. In learning music, there are aspects of the learning process that fall under the routine tasks category. Rewards should boost performance for specific tasks such as repeats with specific goals. The joy of making music and the natural curiosity of a child discovering new sounds can be overshadowed by the mundane repeats required to perfect a skill. But to give a child a reward for doing well in an exam, or time spent on an instrument (no matter HOW that time is spent) could backfire. Intrinsic motivation such as the joy of mastering a skill, of being able to express oneself, or the joy of hearing the difference between what one did a year ago compared to now, the joy of discovering a color of a composer etc... should be enough to keep the joy of music making alive. Parents, choose your rewards carefully. Don't extinguish the fire of learning to grow. Don't fuel the fire of learning to get a prize. __________________________________________________________________________ Notes:

I have encountered beginner adults who have not learned how to read notes. Some learned through youtubes, websites, and some have only taken a one credit class in music theory, from the very basic staff to the major scale. Many have great ears. One of my adult students picked up "Girl with the flaxen hair" Debussy prelude by ear.

In the history of mankind, when oral traditions were replaced by written ones, orators gave way to scribes. Yet back then, the Greek written words had no space between them. Written texts were merely used to remind readers what they already heard. Learning was dependent on comprehension and memory. Music notation started in the same way, from imprecise neumes in Gregorian chants to overly prescribed articulation, dynamic and pacing symbols. As humans controlled more and more the environment, they specialized, and interpreters were separated from composers. We now rely on someone else playing the music for us to listen to, because they are "experts." Performers rely on someone writing the music to play. Learners rely on their eyes before their ears, because publishers are the "experts." Charles Hicks in the 1980s published in the Music Educator's Journal "Sound before Sight, strategies for teaching music reading." The advice is logical, it emphasized continuity, repetition, repeated patterns, narrow range and same key signature. It's a constructivist approach. His recommendation was to explore the PRINCIPLES of notation rather than the SYSTEM of notation. Hidden in the writing of symbols are organized SOUND. If one can help a student first notice how sound perception can be organized (in time, in pitch in volume, in attack, or in structure) before one introduces them to the written notation, it would help contextualize the purpose of learning the symbols. For example, this is double slower, or double faster. This is getting gradually slower versus this is a change of speed. Babies learn to talk by imitation. Why should one learn written music before one learns musicianship? how to feel a regular beat, an upbeat, or a syncopation; what is the difference between a feel of two - or three? how to recognize the feel of a sad mode- or a happy mode? how to slow down or accelerate in gesture? Our music education system puts a lot of weight on the Oral, less on the Aural tradition; it is leaned toward the visual rather than the audio part of learning music. Folk or Art music around the world are, for the most part, still transmitted by oral tradition. In these traditions, even when written down, learning music required close encounter with an instructor, because learning is through exposure, enculturation and imitation. In India, a novice just listens for a year before attempting to improvise lightly a scale (raga). Years can pass before he or she is allowed to imitate licks of the teacher. Here in the U.S., there are students who, after 5 to 7 years of lessons and practice, get technically proficient but barely go to one concert a year. With certain instrument, such as the trumpet, hearing the sound is extremely important as the same buttons may be pressed, but the way one blows determines the pitch. In order to know whether or not one has blown the right pitch, one has to hear it first. Why don't we learn piano the same way? Less like a typewriter, more like a musical instrument. How many of us teachers have encountered a student that played Ode to Joy with the dotted quarter note - eighth note instead of the written quarter notes? They are guided by what they hear on the inside. Most beginner piano books start with what they consider standard repertoire that everyone should know, such as Mary had a little lamb, Jingle bell and so forth. But they publishers changed the rhythm! This repertoire is also not updated nor culturally relevant. The Mexican Hat is not what Mexican Americans listened to, and not all of us know "Oh When the Saints" or Dvorak's symphony, but many will know the latest Lady Gaga, Pentatonix or Disney movie. If the point is to teach something familiar and already in students' ears, then we need an online continuously updated book for the younger generation. One where they can go in and choose songs they know, arranged for different levels, and print out song by song as they progress and taste changes. As for the different types of arrangements one can do for each song with a chord chart, this can be learned in workshops, webinars, or online conferences. Technology can be used to bring the music learning methods to the 21st century. Parents often asked "How do I get my child to practice more without nagging?"

A question for them is "Do you believe that nagging brings results? Do you also nag for your child to do other tasks, such as eating veggies or doing homework?" As a parent & a musician, I did not want my children to associate playing an instrument with a chore, and so we would only teach them when they wanted it and asked us to teach them. This did not work out well, for from the age of five to ten, we only taught one lesson per year. On the other hand, they were exposed to our modeling. We played and sung music quite often. Music making was a joy. They sung along, they were improvising on an instrument or singing secondary voices spontaneously without any nagging from us. This is why this Academy offers music for early childhood development called Music Together. Babies and toddlers are exposed to their caregivers singing and moving to music. This positive role modeling will carry the child very far in terms of their success in music. A child that believes he or she WILL spend a lot of time in music practice will succeed more than a child who believes this "music" activity is a temporary stage. This has nothing to do with their amount of practicing. The comparison was done with children practicing the SAME amount of time, over a period of ten years! A published article about this research is on my personal website, www.banglangdo.com, called "It's all in the Idea." So the question for parents will be this: "What is your thought regarding this musical activity that you are paying for your child to learn?" "Are you reinforcing the idea that daily musical practice is a chore like washing dishes? It just needs to be done until they're old enough to decide?" We all have thought habits. Being musician I am more aware of the ones regarding music. Is your child taking music lessons because of cultural norms, or is it an intrinsic value in your life? Do you listen to music in the car or at home? Do you bring your child to live musical events? Do you spend time on your phone while sitting at your child's lesson or do you sit in to listen and participate in the learning? These beliefs have a major impact on how invested your child will be in their practice at home. The nagging can stop when they see your love of music, or your investment in the activity they do. After a certain minimum level of required practice, it is not the amount of time one spends in music practice that matters, it is HOW one practices. Mindless repeats without a clear goal will only reinforce bad habits, and habits can be physical and auditory. Asking a student "So which sections do you think you need to work on and why?" will force them to put on their thinking cap and reflect. Adding "Where specifically did you hesitate and how can you solve this problem" will develop their critical thinking skills. To be engaged in Mindfulness in music: "Deep practice," is never boring. There is always a small goal to achieve. When it is achieved there is another small goal to set. Just one simple step at a time.

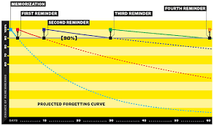

Yet there is a limit on how much “Deep Practice” human beings can do in a day. Ericsson’s research shows that “most world-class experts-including pianists, chess players, novelists, and athletes- practice between three and five hours a day, no matter what skill they pursue.” This is probably because “Deep Practice” would have drained our brain power, and our concentration would be diminished after three hours. Thus for younger students, if you are NOT mentally tired after an hour, then you did not practice very deeply. If we were truly in “Deep Practice” we should also have the impression of continuing to rehearse the material we just learned while we rest. Students have told me that they dream about their music pieces after intense rehearsal sessions. Research suggests that when rehearsals are spaced out, the brain uses that rest period to consolidate that new information or skill and transfer it into long term memory. When studying alone, it is hard to push oneself out of our comfort zone to get into this “Deep Practice” zone. Our brain likes to zone out and let automaticity take over. This happens to some of us when we drive and take a wrong turn because that is a turn we often took. Or we eat without knowing we are eating because we are reading, or on a phone, or playing an app. To be in "Deep Practice" is to do ONE thing at a time, but REALLY WELL. Sometimes it takes an outside source, a teacher, a peer, or even an object, such as a random alarm, to help us realize that we were zoning out. Perhaps it is time to stretch? to check our posture? to REALLY listen? Read these two columns, one at a time; allow 5 seconds in between. A B milk/juice br_ad / b_tt_r chair/table d-sk / c-mp-t-r banana/pear ap--e / or-n-e Now without looking at any column, try to remember as many pairs of words as you. say them out loud. From which column did you recall more words? A or B? Did you have more difficulty reading column B than column A? If you are like most people, you will remember more from column B. Studies show you’ll remember three times as many. “Deep Practice” is a term Daniel Coyle used in his book, The Talent Code.“Deep Practice is built on a paradox: struggling in certain targeted ways - operating at the edge of your ability where you make mistakes- makes you more efficient.” 1 In the previous example, the mere fact of making an effort to read is enough to mark a larger imprint on our memory. “We think of effortless performance as desirable, but it’s really a terrible way to learn,said Robert Bjork,” 2 the chair of the psychology department at U.C.L.A. Students will learn best when they are forced to make an effort, when they allow themselves to make mistakes. This attitude is crucial for a learner‘s resilience. In addition, learners’ tendencies to persist in the face of difficulty are strongly affected by whether they are “performance oriented” (fixed mindset) or “learning oriented” (growth mindset).3 When a mistake becomes an opportunity for learning and problem solving, students will strive to do better every time because they do not believe that they lack "talent," or "intelligence". They believe their learning capability can grow. Hence, how many retakes of an exam should a teacher give? In the music realm, the competition system is set up in such a way that musical students who have more anxiety performing in public will most likely perform at 70% in their first attempt. Shouldn't there be another system that allows second chances? Another example of giving students a chance: after a teacher asks a question, how many seconds should he or she wait before giving out the answer? Cognitive science research seems to indicate that giving students the chance to make a mistake in a low stake situation is a more effective way to help them learn. They will remember much more as well as gain problem solving skills because they were allowed enough time to reflect. With this way of teaching, students will also learn to overcome mistakes, learn about the way their memory works, and develop a growth mindset because they are NOT afraid to make a mistake- as long as they can correct it with guidance, with enough time and practice. Most music teachers would agree that after a certain minimum level of required practice, it is not the amount of time one spends in music practice that matters, it is the way one practices. Yet there is a limit for how much “deep practice” human beings can do in a day. Anderson Ericsson’s calls it "deliberate practice". His research shows that “most world-class experts-including pianists, chess players, novelists, and athletes- practice between three and five hours a day”4 More than 3 hours of “deep practice” would have drained our brain power, and we would not be able to concentrate as efficiently. If we were truly in “deep practice” we should also have the impression of continuing to rehearse the material we just learned while we rest, such as taking a walk, a bath, or a nap. Students have told me that they dream about their music pieces after intense rehearsal sessions. Research suggests that when rehearsals are spaced out, the brain uses that rest period to consolidate that new information or skill and transfer it into long term memory.5 In other words, we need LOTS of reminders. Thus, for many students, it is better to break practice time into shorter sections. Rather than an hour straight at the instrument, it would be most efficient to practice 20 minutes in the morning, 20 minutes right after school, and 20 minutes before bed. It's important to remember that each practice session has a particular focus: its own warm up, technical or musical problems to solve, and "play through". When practicing alone, it is VERY hard to push oneself out of our comfort zone to get into this “deep practice” zone. It requires a lot of self-monitoring and awareness. When we repeat without a clear goal, we tend to zone out and let automaticity take over. Our brain likes to be on automatic pilot. We all daydream. For example, when we drive and take a wrong turn because that is a turn we often took! Often, it takes an outside source, a teacher, a peer, or even an object, such as a random alarm set on our phone, to help us realize that we were zoning out. David Kahneman, in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, cited an experiment which proved that the initial “effort” we make, even unconsciously, can make our mind jump to a higher level of engagement of the brain: In one experiment, the same test questions were either badly printed or well printed.6 This simple visual difference resulted in a wide variance in students’ scores. Students faced with the badly printed questions were better at answering tricky questions than the ones who had an easier time deciphering the exact same questions! Why? The initial effort made to read the badly printed words engaged their brains, and prepared them to think harder. Experiments in skill development find that humans tend to plateau after a certain point. One example of this is in speed typing. In the 1960s, psychologists Paul Fitts and Michael Posner described three stages anyone goes through in acquiring a new skill. The first stage called the “cognitive stage” is when one intellectualizes the task and finds strategies to accomplish things more efficiently. 7 The second stage, the “associative stage,” is when one is comfortable enough and spends much less energy concentrating and making fewer major errors. The third stage, called the “autonomous stage,” is when one plateaus and most skills learned are now running on automatic pilot. The latest research on neuron myelin building suggests that we are built to automatize skills as soon as we can. “The more we develop a skill circuit [in our neurons], the less we’re aware that we’re using it.”8 As soon as a particular skill is getting easier, another part of the brain, the cerebellum, is taking over this more or less automatized task, and we have more brain power to devote to other tasks. In fact, the latest research on neuron myelin building suggests that we humans are built to automatize skills as soon as we can. “The more we develop a skill circuit [in our neurons], the less we’re aware that we’re using it.”8 When one can be on automatic pilot Csikszentmihalyi calls it the feeling of effortlessness, flow, or “in the zone”. Flow theory is now a common word in positive psychology. But Deep Practice is to prevent us from getting to that automatic stage. It is more like a laser-sharp pointed mind, like sitting on the edge of a fence, where balance is crucial. In order to prevent this automaticity and remain in the “deep practice” zone, teachers will have to come up with many ways to engage their students at the right level, scaffolding on what they already know. Since Deep Practice is a way to develop more efficient learning, and it can be practiced, it follows that continuous Deep Practice will build a growth mindset. Students with fixed mindset will tend to take feedback very personally, they avoid failures and challenges because they want to perform well, so they stick to what they know. Students with a growth mindset will “go out on a limb because that’s where the fruit is”, 9 they embrace challenges, they are not afraid to make a mistake because they know these are opportunities to learn; they take constructive feedback as an assessment of their current state, and they believe they can learn to do better. In order to build self-efficacy and life long learners, teachers should encourage growth mindsets and give students opportunities to reflect on how they learn, to understand how mistakes occur, and guide them to find solutions.

|